In the last shot of "The Searchers," the camera, from deep inside the cozy recesses of a frontier homestead, peers out though an open doorway into the bright sunshine. The contrast between the dim interior and the daylight outside creates a second frame within the wide expanse of the screen. Inside that smaller space, the desert glare highlights the shape and darkens the features of the man who lingers just beyond the threshold. Everyone else has come inside: the other surviving characters, who have endured grief, violence, the loss of kin and the agony of waiting, and also, implicitly, the audience, which has anxiously anticipated this homecoming. But the hero, whose ruthlessness and obstinacy have made it possible, is excluded, and our last glimpse of him emphasizes his solitude, his separateness, his alienation — from his friends and family, and also from us.

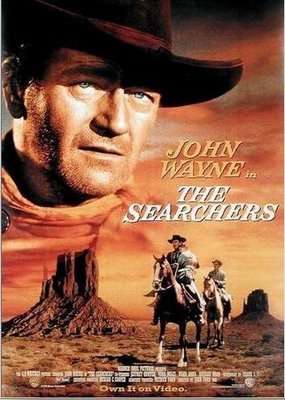

In the last shot of "The Searchers," the camera, from deep inside the cozy recesses of a frontier homestead, peers out though an open doorway into the bright sunshine. The contrast between the dim interior and the daylight outside creates a second frame within the wide expanse of the screen. Inside that smaller space, the desert glare highlights the shape and darkens the features of the man who lingers just beyond the threshold. Everyone else has come inside: the other surviving characters, who have endured grief, violence, the loss of kin and the agony of waiting, and also, implicitly, the audience, which has anxiously anticipated this homecoming. But the hero, whose ruthlessness and obstinacy have made it possible, is excluded, and our last glimpse of him emphasizes his solitude, his separateness, his alienation — from his friends and family, and also from us.Even if you are watching "The Searchers" for the first time — perhaps on the beautiful new DVD that Warner Home Video has just released to mark the film's 50th anniversary — this final shot may look familiar. For one thing, it deliberately replicates the first image you see after the opening titles — a view of a nearly identical vista from a very similar perspective. Indeed, the frame-within-the-frame created by shooting through relative darkness into a sliver of intense natural light is a notable motif in this movie, and elsewhere in the work of its director, John Ford. Especially in his westerns, Ford loved to create bustling, busy interiors full of life and feeling, and he was equally fond of positioning human figures, alone or in small, vulnerable groups, against vast, obliterating landscapes. Shooting from the indoors out is his way of yoking together these two realms of experience — the domestic and the wild, the social and the natural — and also of acknowledging the almost metaphysical gap between them, the threshold that cannot be crossed.

But that image of John Wayne's shadow in the doorway — he plays the solitary hero, Ethan Edwards — does not just pick up on other such moments in "The Searchers." Perhaps because the shot is thematically rich as well as visually arresting — because it so perfectly unites showing and telling — it has become a touchstone, promiscuously quoted, consciously or not, by filmmakers whose debt to Ford might not be otherwise apparent. Ernest Hemingway once said that all of American literature could be traced back to one book, Mark Twain's "Huckleberry Finn," and something similar might be said of American cinema and "The Searchers." It has become one of those movies that you see, in part, through the movies that came after it and that show traces of its influence. "Apocalypse Now," "Punch-Drunk Love," "Kill Bill," "Brokeback Mountain": those were the titles that flickered in my consciousness in the final seconds of a recent screening in Cannes of Ford's masterwork, all because, at crucial moments, they seem to pay homage to that single, signature shot.

At the end of "Brokeback Mountain," for instance, we are inside Ennis Del Mar's trailer, looking out the window onto the Wyoming rangeland, from a domestic space into the wilderness, as in "The Searchers." But in this case, the interior, rather than a warm, buzzing home, is barren, the scene of Ennis's desolation. The outside, insofar as it recalls the mountain where he and Jack Twist spent their youthful summer of love together, is an unattainable place of freedom and companionship, rather than a zone of danger and loneliness as it was in the earlier film. Ennis is severed from those he loves, and from his own nature, by the strictures of civilization, while Ethan's violent nature renders him an exile from civilized life, condemned to wander on the margins of law, stability and order.

Of course, "Brokeback Mountain" is a western by virtue of its setting rather than its themes, which recall the forbidden-love mid-1950's melodramas of Douglas Sirk more than anything Ford was doing at the time. But just about any movie that ventures into the territory of the western — and a great many that do not — has a way of bumping up against not only Ford's images but also his ideas.

He did not invent the genre, of course, and hardly restricted himself to it in the course of a career that began in the silent era and lasted more than 50 years. There will always be those who find the frontier visions of Budd Boetticher, Anthony Mann, Raoul Walsh and Howard Hawks more complex, more authentic or more varied than Ford's, as well as those who seek out western heroes less obvious than John Wayne. But like it or not, Wayne and Ford, whose long association is sampled in a new eight-movie boxed set and examined in a recent PBS documentary, "John Ford/John Wayne: The Filmmaker and the Legend," directed by Sam Pollard, have long since come to represent the classic, canonical idea of the American West on film.

Which is to say that their movies, however deeply revered and frequently imitated, have also been attacked, mocked, dismissed and misunderstood. If, from the late 1930's to the early 1960's, they defined the classic western — a tableau involving marauding Indians, fearless gunslingers, ruthless outlaws and the occasional high-spirited gal in a calico dress — they also begat the countertendency that came to be known as the revisionist western, with its nihilism, its brutality and its harsh demystification of the threadbare legends of the old West. Thus, after Sam Peckinpah and Sergio Leone, after "McCabe and Mrs. Miller" and "Unforgiven," after "Dead Man" and "Deadwood," the brightly colored black-and-white world of "The Searchers" might look quaint, simplistic and not a little retrograde.

It certainly looked that way at Bennington College in 1982, when the novelist Jonathan Lethem saw the film for the first time. He recalls the laughter of his fellow undergraduates in an essay called "Defending 'The Searchers,' " which also recalls his own earnest intellectual obsession with the film. His first attempt to appreciate it ends in defeat — " 'The Searchers' was only a camp opportunity after all. I was a fool" — but he keeps returning to contend with the sneers and shrugs of academic and bohemian friends and acquaintances, who can't see what he's so excited about. "Come on, Jonathan," one of them says, "it's a Hollywood western."

So it is, which means that it's open to the usual accusations of racism, sentimentality and wishful thinking. David Thomson, in his "Biographical Dictionary of Film," tips his hat to "The Searchers," but only in the midst of a thorough ideological demolition of its director, whose "male chauvinism believes in uniforms, drunken candor, fresh-faced little women (though never sexuality), a gallery of supporting players bristling with tedious eccentricity and the elevation of these random prejudices into a near-political attitude." The idea that Ford is an apologist for violence and a falsifier of history, as Mr. Thomson insists, dovetails with a longstanding liberal suspicion (articulated most fully by Garry Wills in his book "John Wayne's America") of Wayne, one of Hollywood's most outspoken conservatives for most of his career. And of course, the presumed attitudes that make Wayne and Ford anathema at one end of the spectrum turn them into heroes at the other.

But as the PBS documentary makes clear, the two men did not always march in political lockstep. And in any case, the closer you look at the movies themselves, the less comfortably they fit within any neat political scheme. Even the portrayal of Indian and Mexican characters, once you get past the accents and the face paint, cannot quite be reduced to caricature.

And Wayne himself, from his star-making entrance as the Ringo Kid in "Stagecoach" (1939) to his valedictory performance in "The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance" (1962), his last western with Ford, is hardly the simple personification of manly virtue his critics disdain and his admirers long for. Even when he drifts toward playing a John Wayne type rather than a fully formed character, there is enough unacknowledged sorrow in his broad features, and enough uncontrolled anger in that slow, hesitant phrasing, to make him seem dangerous, unpredictable: someone to watch. He is never quite who you think he will be.

And this is never truer than in "The Searchers," where much about Ethan's personality and personal history remains in the shadows. A former soldier in the Confederate Army, he arrives in Texas (though the film was shot in Monument Valley in Utah) three years after the end of the Civil War, with no way of accounting for the time lag apart from the angry insistence that he didn't spend it in California. Wherever he was, he acquired both a virulent hatred of Indians and an intimate understanding of their ways. When his two young nieces are kidnapped by Comanches — their parents and brothers are scalped and the farmstead burned — he sets out on a search that will last for years and that will blur the distinction between rescue and vengeance. It becomes clear toward the end that he wants to find the surviving niece (now played by Natalie Wood) so that he can kill her.

This impulse points to a terrifying, pathological conception of honor, sexual and racial, and for much of "The Searchers" Ethan's heroism is inseparable from his mania. To the horror and bafflement of his companions (one of whom is both a preacher and a Texas Ranger, and thus a perfect embodiment of civilized order), Ethan shoots out the eyes of a dead Comanche, and exults that this posthumous blinding will prevent this enemy from finding his way to paradise. But when you think about it, Ethan's ability to commit such an atrocity rests on a form of respect, since unlike the others he not only knows something about Comanche beliefs but is also willing to accept their reality. And the film, for its part (the script is by Frank S. Nugent, who was once a film critic for The New York Times before he took up screenwriting), acknowledges the reality of Ethan's prejudices and blind spots, which is not the same as sharing or condoning them.

The Indian wars of the post-Civil War era form a tragic backdrop in most of Ford's post-World War II westerns, much as the earlier conflicts between settlers and natives did in the novels of James Fenimore Cooper. That the Indians are defending their land, and enacting their own vengeance for earlier attacks, is widely acknowledged, even insisted upon. The real subject, though, is not how the West was conquered, but how — according to what codes, values and customs — it will be governed. The real battles are internal, and they turn on the character of the society being forged, in violence, by the settlers. Where, in this new society, will the frontier be drawn between vengeance and justice? Between loyalty to one's kind and the more abstract obligations of human decency? Between the rule of law and the law of the jungle? Between virtue and power? Between — to paraphrase one of Ford's best-known and most controversial formulations — truth and legend?

Ford's way of posing these questions seems more urgent — and more subtle — now than it may have at the time, precisely because his films are so overtly concerned with the kind of moral argument that is, or should be, at the center of American political discourse at a time of war and terrorism. He is concerned not as much with the conflict between good and evil as with contradictory notions of right, with the contradictory tensions that bedevil people who are, in the larger scheme, on the same side. When should we fight? How should we conduct ourselves when we must? In "Fort Apache," for example, the elaborate codes of military duty, without which the intricate and closely observed society of the isolated fort would fall apart, are exactly what lead it toward catastrophe. Wayne, as a savvy and moderate-tempered officer, has no choice but to obey his headstrong and vainglorious commander, played by Henry Fonda, who provokes an unnecessary and disastrous confrontation with the Apaches. In the end, Wayne, smiling mysteriously, tells a group of eager journalists that Fonda's character was a brave and brilliant military tactician. It's a lie, but apparently the public does not require — or can't handle — the truth.

In telling it, Wayne is writing himself out of history, which is also his fate in "The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance" (not, unfortunately, one of the discs in the Warner box). That film — which contains the famous line "When legend becomes fact, print the legend!" —throws Wayne's man of action and James Stewart's man of principle into a wary, rivalrous alliance. Their common enemy is an almost cartoonish thug played by Lee Marvin, but the real conflict is between Stewart's lawyer and Wayne's mysterious gunman, one of whom will be remembered as the man who shot Liberty Valance.

What we learn, in the course of the film's long flashbacks, is that the triumph of civilization over barbarism is founded on a necessary lie, and that underneath its polished procedures and high-minded institutions is a buried legacy of bloodshed. The idea that virtue can exist without violence is as untenable, as unrealistic, as the belief — central to the revisionist tradition, and advanced with particular fervor in HBO's "Deadwood" — that human society is defined by gradations of brutality, raw power, cynicism and greed.

If only things were that simple. But everywhere you look in Ford's world — certainly in "Fort Apache," in "The Searchers," in "The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance" — you see truth shading into lie, righteousness into brutality, high honor into blind obedience. You also see, in the boisterous emoting of the secondary characters, the society that these confused ideals and complicated heroes exist to preserve: a place where people can dance (frequently), drink (constantly), flirt (occasionally) and act silly.

And everywhere else — after Ford, beyond his movies — you find the same thing. The monomaniacal quest for vengeance, undertaken by a hero at odds with the society he is expected to protect: it's sometimes hard to think of a movie from the past 30 years, from "Taxi Driver" to "Batman Begins," that doesn't take up this theme. And the deeper question of where vengeance should stop, and how it can be distinguished from justice, surfaces in "Unforgiven" and "In the Bedroom," in "Mystic River" and "Munich."

In "Munich" the Mossad assassins spend most of the film in a limbo that Ethan Edwards would recognize, even though it takes place amid the man-made monuments of Europe rather than the wind-hewn rock formations of Monument Valley. The Israeli agents are far from home, exiled from the democratic, law-governed society in whose name they commit their acts of vengeance and pre-emption, and frighteningly close both to their enemies and to a state of pure, violent retaliatory anarchy. With more anguish, perhaps, than characters in a John Ford movie, they often find themselves arguing with one another, trying to overcome, or at least to rationalize, the contradictions of what they are doing. They appeal to various texts and traditions, but they might do better to pay attention to the television that is on in the background at one point in the movie: another frame within the frame, tuned, hardly by accident, to "The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance."

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário